- Home

- Jerry Spinelli

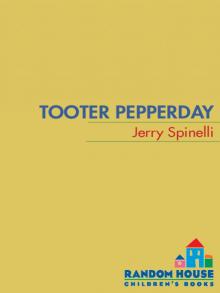

Tooter Pepperday: A Tooter Tale Page 3

Tooter Pepperday: A Tooter Tale Read online

Page 3

Tooter grunted.

Aunt Sally walked over to a small group of trees and shrubs. “Second thing. See these plants with leaves that look like mittens?”

Tooter grunted. The leaves did look like mittens.

“They’re called sassafras,” said Aunt Sally. “Someday I want you to pull up one of those plants and smell the root.”

“What is it?” sniffed Tooter. “A poop root?”

Aunt Sally laughed. “You’ll find out.”

At dinner that evening Tooter would not eat any vegetables or drink her milk. “Why does everything on a farm have to smell bad?” she grumped. “Everywhere you go, poop here, poop there. I’ll bet the bees are even flying over and pooping in our hair.”

Chuckie laughed.

Tooter went on talking about poop. Bee poop. Goat poop. Pig poop. Chicken poop.

Finally Mrs. Pepperday slammed down her fork.

“You’ve said the word poop twenty-two times,” said Mr. Pepperday.

“Poop poop poop poop poop,” said Tooter.

“That’s twenty-seven.”

“If you say that word one more time,” said Mrs. Pepperday, “you may leave the table and go outside to smell the farm some more.”

“Poop,” said Tooter.

Chuckie cracked up.

Mrs. Pepperday pointed to the door. Tooter left the room.

“Did you turn the egg today?” Mrs. Pepperday called.

“Yes,” Tooter called back, and was gone.

Ten minutes later Aunt Sally looked out the window and broke out laughing.

She waved. “Come here. You gotta see this.”

Everyone went to the window. There was Tooter, in the barnyard. She was wearing Aunt Sally’s straw hat on her head and a clothespin on her nose. She was running back and forth with a can of air freshener. She was spraying the farm.

10

Countdown to Hatch

Tooter went to bed that night. But she could not sleep. She had lied to her mother. She had not turned the egg that day.

At first, she had felt fine about it. But now she kept hearing Aunt Sally’s words. If you don’t do your chore, the egg will never become a chick.

Never become …

Never become …

She could not stand it any longer. She got out of bed. She opened her door. The house was dark. And scary.

She slid her hand along the wall. She felt her way down the hall to the stairs.

She lowered herself onto one step. Then another. Halfway down the stairs, she began to see something. A faint misting of light.

She came to the bottom. She made her way through the living room. The light was still very faint. Her hands groped before her. In the dining room she could make out the tops of chairs and furniture.

And the glowing doorway to the kitchen.

There it was. One small bare bulb in the corner of the kitchen. Sixty watts of light in a world of darkness. And the egg basking like a sunbather on the beach.

On the side of the shoebox Aunt Sally had made a sign. In red crayon were the words DAYS TILL HATCH. Then came a piece of paper with a number. The number was 14.

Tooter screeched: “Fourteen days to go!” She clamped her mouth shut. Had she woken someone up?

She glared at the egg.

She whispered, “Are you crazy? I’m not turning you for fourteen more days. What do I look like? Your mother?”

She jabbed her finger at the egg. “Three more days … okay, four … o-kay, five. That’s it. Counting today. If you ain’t out in five days—” she pressed the egg with her fingertip “—you can turn yourself.”

She gave the egg a quarter-turn. She started to leave, and discovered she did not want to go. It was warm and bright where the light bulb was. Safe and friendly. She wished she was small enough to crawl into the shoebox with the egg.

But she wasn’t.

Tooter looked at the kitchen window, at the blackness beyond. She looked at the back door. Was it locked? Was someone, some thing even now reaching for the doorknob, about to look in the window?

She got out of there—fast. She groped and bumped and stumbled her way back through the dining room and living room and up the stairway and down the hallway to her room. She plunged into her bed and cuddled and curled till her nose met her knees and pulled the sheet over herself like a shell and shivered herself to sleep.

11

Better Be Careful

Several days later Tooter was outside teaching Chuckie how to spit long-distance.

“Tooter!” called Mrs. Pepperday.

Her mother was waiting in the kitchen. She had a scowl on her face.

She pointed to the shoebox. “Is this your doing?”

“Is what?” said Tooter.

“You know what,” said her mother. “Don’t act innocent.”

Tooter walked over to the shoebox. The sign now said 11 days till hatching. She looked in. There was the egg, dozing on its side.

But there was a second egg too. Standing in the corner. With a face. A terrible face drawn in crayon. A face with a wicked mouth and green, daggery teeth. A face with purple skin and horns. A face with eyes yellow and evil. Eyes that glared at the other egg.

“What is it?” said Tooter. “Some kind of voodoo egg?”

“Funny you should say that,” said her mother. “I was thinking the same thing. It looks like someone is trying to cast a spell on the good egg.”

Tooter stared at her mother. “Who would do that?”

Her mother squeezed Tooter’s cheeks until her mouth was like a fish’s. “You would do that, little miss, because you don’t like it here. So you’re trying sabotage.”

“What’s sabotage?” said Tooter through her fish mouth. She hated having her cheeks squeezed.

“Sabotage,” said her mother, “is messing things up so you can get your own way. Like sneaking into your father’s computer and sticking yourself into his story. Like putting a pair of my earrings on Harvey’s ears.”

Tooter looked shocked. “You think I did all that?”

Her mother snorted. “No, I think the tooth fairy did it.” She let go of her daughter’s cheeks. She took the voodoo egg from the box and gave it to Tooter. “Throw this on the compost heap.”

Tooter screeched, “I hate the compost heap!”

Her mother pointed to the door.

“Do I have to do it if I confess?” said Tooter.

“Yes.”

Tooter stomped her foot, stuck her tongue out at the good egg, and left.

Tooter hated it when her mother had everything figured out. What was the point of confessing? She was glad she didn’t.

And now she had a name for her recent activities: sabotage. That was interesting.

Tooter headed for the compost heap. She had a great idea. She didn’t have to get near enough to smell it. All she had to do was pitch the egg from a safe distance. Which she did.

The egg fell short.

Tooter pinched her nose, stomped up to the wire fence and threw the egg over. At least it was hard-boiled.

Walking away, Tooter spotted the white-topped weeds. The ones Aunt Sally had called Queen Anne’s lace.

Look real close at one, and see what you find in the middle.

Tooter picked one out. She looked. It was lacy, all right. Like a doily. Round. The size of a small pancake.

She knelt down to look closer. There was a faint odor of carrots. Yes, there was something in the middle of the lace. A spot. A fleck. So small you’d never notice unless you got this close.

The spot was black—no, purple. She looked closer, squinting, straining her eye-balls.

It was a flower.

The teeniest, tiniest flower she had ever seen. It would take a whole bouquet of them to cover her fingernail. An almost-invisible purple flower keeping its secret in a white, carroty bed of lace.

“Wow.”

What else had Aunt Sally said?

Pull up one of those plants and smell the ro

ot.

Mitten-shaped leaves. Sassafras. She found one. She pulled it from the earth. The root didn’t look different from any other root. She smelled it. She took off running.

She found Aunt Sally in the barn.

She wagged the root under her nose. “Root beer!”

Aunt Sally smiled. “Root beer it is. And did you find anything in the Queen Anne’s lace?”

“Sure did,” said Tooter. “A purple flower. The world’s littlest.”

Aunt Sally shook her finger at Tooter. “Better be careful, or you might become a farmer.”

“No way,” said Tooter, laughing.

At dinner Mr. Pepperday said, “You know, that egg in there has been in the family for a while now. Don’t you think we ought to give it a name?”

“Humpty Dumpty!” blurted Chuckie.

“Arf!” said Harvey.

“Bubblebutt,” said Tooter.

“Eggbert,” said Mr. Pepperday.

The three grownups agreed. Eggbert it was.

“Now, remember everybody,” said Aunt Sally. “When the time comes, no giving Eggbert a helping hand. Chicks have to fight their way out of the shell. That’s how they get the gumption to take on the world.”

Aunt Sally poured herself a glass of milk.

“And another thing,” she said. She took a long swallow from her glass. “The first critter it sees when it comes out of that shell, that’s who it’s gonna call Mama.”

Chuckie laughed. “Maybe it’ll be Harvey!”

Harvey arfed.

Tooter said nothing. It was not until after dinner that she realized she had eaten her vegetables.

12

Two Tooters

Nine days till hatching …

Eight days …

Seven days …

Day after day Tooter heard: “Did you turn Eggbert? Did you turn Eggbert?” It was worse than “Did you brush your teeth?”

She wished everybody would stop nagging her. Maybe then she could figure out if she liked the darn thing or not.

Sometimes it seemed there were two Tooters now. One Tooter, the old one, hated having only two TV channels. The new Tooter went out each day to look at the tiny purple flowers.

The old Tooter held her nose and went “Eww!” every time she passed the barn. The new Tooter breathed deeply and went “Ahh!” as she boiled sassafras roots with Aunt Sally.

The old Tooter would not go near goat’s milk. The new Tooter drank chocolate goat’s milk for breakfast.

The old Tooter listened each evening for the ring of the Jack and Jill truck. The new Tooter heard the song of a meadowlark.

The old Tooter turned off Eggbert’s light. The new Tooter turned it right back on.

Three days …

Two days …

And then the old Tooter went away and never came back. It happened with one day left till hatching. And it happened in the barnyard.

Besides turning Eggbert, Tooter had another chore that day. She had to feed the chickens. Aunt Sally had given her a can of seeds and cracked corn.

In the barnyard she walked about casting feed onto the ground. Five chickens and the rooster came cackling and pecking.

One of the chickens was busily pecking away when another chicken charged and sent it squawking. There was a flurry of brown feathers. The bully chicken started pecking in the other’s place.

Tooter recognized the bully. It was Drumsticks, the hen that laid Eggbert.

Now it was Tooter who came charging. “Who do you think you are? You’re not just dumb—you’re mean!”

Drumsticks squawked and fled.

Tooter went after her. “You ought to be ashamed of yourself! There’s an egg in that house and it’s supposed to be yours and you don’t even care! What kind of a mother are you?”

Tooter chased the chicken in circles till she got dizzy and gave up. Drumsticks went back to pecking as if nothing had happened. As if feeding her own gizzard was all that mattered in the world.

Tooter knew that her own mother would never be so heartless.

And Tooter knew what she had to do.

13

The Longest Night

Before going to sleep that night, Tooter set her Yogi Bear alarm clock on Spring. That meant twelve o’clock midnight.

When the alarm went off, she couldn’t believe she had been asleep for three hours. It felt like three minutes.

She dragged herself out of bed. This time she had a flashlight waiting. She followed the beam of light down the dark hallway, down the stairs, through the living room and dining room to the kitchen.

She looked into the shoebox and let out a squeal of joy. It had already begun. The shell on one end was cracked.

Tooter squealed again as the shell wobbled slightly. The crack grew a bit. She thought she saw the end of a tiny beak.

Tooter lay down on her stomach. She propped her chin in her hands and smiled and watched. Every minute or so she giggled.

It amazed her to think that inside that smooth, brown shell, an egg had become Eggbert.

Tooter remembered Aunt Sally’s words. No giving Eggbert a helping hand.

But Aunt Sally did not say you couldn’t root for it.

Tooter made a fist.

“Come on,” she whispered. “You can do it.”

The crack grew slowly. Tooter’s sleepy eyes kept closing and snapping open. The crack became a circle. The shell now had a lid.

Tooter could see the lid move. She knew Eggbert was inside poking with all his might.

“Come on … you can do it.”

Tooter drifted in and out of sleep. She kept seeing herself and Eggbert. They were alike, weren’t they? The two of them? Both taken from their cozy nests and dumped in a strange place. She on a farm, he in a shoebox.

Tooter and Eggbert …

Eggbert and Tooter …

And then her eyes were open again. There he was, poking through a hole in the lid. Half a scrawny face, beak and eye, looking straight up at her.

Somewhere outside the rooster crowed. Night withdrew from the windowpane.

Tooter felt the warmth of the light bulb on her face and in her heart. She smiled weakly. She greeted the newborn chick. “Hi, Eggbert.”

She closed her eyes.

The rest of the family came down for breakfast. They heard the peeping, then saw the fluffy yellow chick. Tooter was curled around the shoebox, fast asleep.

Mrs. Pepperday knelt down and smiled at her daughter. “Miss Tooter, you never cease to amaze me.”

“Looks like Mama and baby are doing fine,” said Aunt Sally.

Chuckie and Harvey sat quietly by the box, looking in.

Mr. Pepperday chuckled. “I think Tooter Pepperday has finally joined the rest of us hogs in the slop.”

About the Author

None of Jerry Spinelli’s six children was ever saddled with the responsibility of babysitting an egg, but his daughter Molly was just as persistent with him as Tooter Pepperday is with her father. While writing one of his books, Jerry didn’t hear his daughter calling him until she sat on his desk and began writing him a note vertically along the page of his longhand manuscript! He told her to “Scoot!” but paid more attention to her next time she came into the room.

Other books by Jerry Spinelli include Blue Ribbon Blues, Stargirl, and Maniac Magee, for which he won the Newbery Medal in 1991. Jerry lives with his wife, Eileen, also a children’s book author, in Pennsylvania.

Don’t miss the next book about Tooter!

“Aunt Sally,” Tooter said, “what’s the goat’s name?”

Aunt Sally scratched her ear. “Guess it don’t rightly have a name. I usually just call it ‘hey you.’ ”

Tooter stepped back to look the goat over. It was the color of dirty white socks before they went into the washer. She was thinking of naming it “Socks” when suddenly she burped. And the burp tasted like last night’s pizza.

“I got it!” she cried. She leaned in nose to nose with the g

oat. “Pepperoni!”

Do you like stories about animals?

Billy looked from one parent to the other. “If you’d just get me a dog for my birthday, I’d be real good.”

Mrs. Getten shook her head. “I think you should be good first.”

“You don’t seem like you’re ready for a dog, son.”

“Not ready? That’s all I ever wanted!”

His father said, “If you’d help around here, maybe we’d consider a dog. But not with the kind of stunt you pulled this morning.”

Billy didn’t dare say what he was thinking. They really should have gotten a dog instead of a baby. What good was a baby? She couldn’t even run after a stick.

Who Put That Hair in My Toothbrush?

Who Put That Hair in My Toothbrush? Stargirl

Stargirl Loser

Loser Jake and Lily

Jake and Lily Wringer

Wringer Maniac Magee

Maniac Magee Smiles to Go

Smiles to Go Love, Stargirl

Love, Stargirl Hokey Pokey

Hokey Pokey Third Grade Angels

Third Grade Angels Tooter Pepperday: A Tooter Tale

Tooter Pepperday: A Tooter Tale Knots in My Yo-Yo String Knots in My Yo-Yo String

Knots in My Yo-Yo String Knots in My Yo-Yo String Blue Ribbon Blues: A Tooter Tale

Blue Ribbon Blues: A Tooter Tale The Bathwater Gang

The Bathwater Gang Crash

Crash Fourth Grade Rats

Fourth Grade Rats Eggs

Eggs Blue Ribbon Blues

Blue Ribbon Blues Knots in My Yo-Yo String

Knots in My Yo-Yo String Dead Wednesday

Dead Wednesday Tooter Pepperday

Tooter Pepperday